The sky is falling - We need a police state!!!!

Agent drank 4 beers night of Waikiki shooting

Source

Agent drank 4 beers night of Waikiki shooting

Associated Press Tue Aug 6, 2013 7:31 PM

HONOLULU — A State Department special agent accused of murder after he shot and killed a man at a Waikiki McDonald’s in 2011 said he displayed his credentials and identified himself as a law enforcement officer in an attempt to diffuse a hostile situation from escalating.

Federal agent Christopher Deedy began testifying in his own defense Tuesday, one month into his trial in the killing of Kollin Elderts of Kailua.

He said Elderts was aggressively bothering a customer. “The way he was acting, I thought there was a possibility he was under the influence of alcohol,” Deedy said of Elderts.

For much of his testimony, he stood up to address the jury, using a pointer to describe footage from the restaurant’s surveillance footage. Deedy said he walked over to Elderts’ table and asked what was going on. Deedy described angry responses laced with expletives.

“He said you’re not going to arrest me, do you have a gun,” Deedy testified Elderts said when he identified himself. “That was not the response I had anticipated.”

Deedy, 29, began by describing his training, saying he started working for the State Department in June 2009. He was in Honolulu to help provide security for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit.

Deedy said Elderts threatened him and called him a haole — the Hawaiian term for a white person — in a derogatory way.

He also testified about his training, relating that to how he handled the McDonald’s situation. “At the time when I intervened, it’s something I learned in training,” He said. “If you intervene when an assault is occurring you’ve already failed at your job.”

When asked by his attorney Brook Hart whether he carries a weapon at all times, Deedy said: “I personally choose to.”

Deedy’s defense lawyers contend that he was acting in self-defense and protecting others during the deadly altercation in the early morning hours at the restaurant.

“Your weapon is a deadly weapon,” Deedy said. “It’s a great responsibility.”

Prosecutors have argued the shooting was caused by intoxication and Deedy’s inexperience. Deedy, from Arlington, Va., was out bar-hopping with friends.

Deedy said he drank “roughly four beers, maybe less,” from about 8:45 p.m. to 2:15 a.m., after flying from Washington, D.C. to Honolulu. He said four is his limit when he’s armed. “I always try to drink responsibly…to keep myself from being under the influence.”

Elderts died of a single gunshot wound to the chest during a fight with Deedy.

Witnesses have testified that Deedy started the fight by kicking Elderts. The defense claims he was protecting a customer from being bullied by Elderts.

“An officer is not required to receive the attack before he uses any defensive maneuver,” Deedy said, describing how agents are trained to assess “pre-assault indicators” including body language.

Deedy often looked at jurors as he explained his training and gave information about his personal life, including that he was born in Worcester, Mass., spent time in Japan and graduated from Tulane University in New Orleans with a degree in economics. He got married in February 2011, months before the deadly encounter on Nov. 5, 2011.

He seemed more relaxed after a lunch break, when he testified about what happened before he arrived at the McDonald’s, even at one point joking about being excited to be able to buy a burger at the airport before his early morning flight and about hearing bad karaoke at a Chinatown bar.

———

Kelleher can be reached on Twitter at http://twitter.com/jenhapa

I also wonder if the nut jobs in Congress were following Gods orders when they passed these draconian laws that make possession of firecrackers and bombs punishable by 20 years in prison.

Man blows up dog, cites rapture, police say

Associated Press Tue Aug 6, 2013 1:20 PM

STEVENSON, Wash. — A Stevenson man accused of blowing up his dog has been charged with a felony.

The Skamania County sheriff’s office says the prosecutor filed charges Monday against Christopher Wayne Dillingham.

The felony is possession of a bomb or explosive device with intent to use for an unlawful purpose. If convicted, the 45-year-old could face up to 20 years in prison. He’s also charged with reckless endangerment.

Dillingham appeared in court Monday in Stevenson and was ordered held on $500,000 bail.

In court papers, investigators said Dillingham attached a fireworks bomb to the dog’s collar early Sunday and set it off with a blast that alarmed neighbors. Dillingham said he killed the dog because an ex-girlfriend had “put the devil in it.” He also said he was preparing for the rapture.

Obama administration authorized recent drone strikes in Yemen

By Greg Miller, Anne Gearan and Sudarsan Raghavan, Published: August 6 | Updated: Wednesday, August 7, 6:51 AM

The Obama administration authorized a series of drone strikes in Yemen over the past 10 days as part of an effort to disrupt an al-Qaeda terrorism plot that has forced the closure of American embassies around the world, U.S. officials said.

The officials said the revived drone campaign — with five strikes in rapid succession — is directly related to intelligence indicating that al-Qaeda’s leader has urged the group’s Yemen affiliate to attack Western targets.

The strikes have ended a period in which U.S. drone activity in the Arabian Peninsula has been relatively rare, with a seven-week stretch with no strikes. The latest strike, in southern Yemen on Wednesday, killed seven alleged militants, the Associated Press reported. A strike on Tuesday reportedly killed four militants in the impoverished nation’s Marib province, a Yemeni security official said.

Although the BBC reported Wednesday that the terror plot had been disrupted,citing statements by Yemeni government officials, U.S. intelligence officials remain skeptical that the danger has passed. One intelligence official said the plot as described by the Yemenis — involving blowing up pipelines and taking over oil and gas facilities — may have been only one component of a broader plan to hit Western targets.

Officials said Tuesday there is no indication that senior al-Qaeda operatives in Yemen have been killed in the drone strikes.

“It’s too early to tell whether we’ve actually disrupted anything,” a senior U.S. official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter. The official described the renewed air assault as part of a coordinated response to intelligence that has alarmed counterterrorism officials but lacks specific details about what al-Qaeda may target or when.

“What the U.S. government is trying to do here is to buy time,” the official added.

The State Department underlined that approach on Tuesday, announcing that it had ordered the evacuation of much of the U.S. Embassy in the Yemeni capital of Sanaa and urged all Americans to leave the country immediately.

In a global travel alert, the State Department said that all non-emergency U.S. government personnel would be removed “due to the continued potential for terrorist attacks.” It described an “extremely high” security threat level in Yemen.

Yemen is the home base of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, the branch of the terrorist group thought to be the most likely to attack U.S. or Western interests. The U.S. Embassy in Yemen was among 19 that were closed through Saturday, as were embassies in Yemen representing several European nations. The British Embassy said Tuesday that it had removed its staff.

The State Department’s decision drew a sharp rebuke from the Yemeni government, which said the evacuation “serves the interests of the extremists and undermines the exceptional cooperation between Yemen and the international alliance against terrorism.”

“Yemen has taken all necessary precautions to ensure the safety and security of foreign missions in the capital,” the Yemeni Embassy in Washington said in a statement.

State Department spokeswoman Jennifer Psaki took issue with Yemen’s assertion that the U.S. move rewards terrorists and said the decision to remove Americans from the country for safety reasons speaks for itself.

At the same time, jihadists took to Web forums to celebrate the closure of the embassies, with some boasting that doing so was a “nightmare” for the United States, according to the SITE Intelligence Group, a nonprofit organization that monitors the forums.

The burst of drone activity provides new insight into the Obama administration’s approach to counterterrorism operations. U.S. officials said the CIA and the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command, which operate parallel drone campaigns in Yemen, have refrained from launching missiles for several months in part because of more restrictive targeting guidelines imposed by President Obama this year. Those new rules, however, allow for strikes to resume in response to an elevated threat.

“They have been holding fire,” said a U.S. official with access to information about the al-Qaeda threat and the drone campaign. But intercepted communications between al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, who is believed to be in Pakistan, and his counterpart in Yemen, Nasir al-Wuhayshi, have raised concern that the network is preparing an assault on Western targets.

“The chatter is coming from Yemen,” the official said. Embassies outside the region were closed not because they were specifically mentioned but because in Yemen and other countries, they would be prominent targets.

A few dozen U.S. Special Operations forces have been stationed in Yemen since last year to train Yemeni counterterrorism forces and to help pinpoint targets for airstrikes against al-Qaeda targets in the country. The U.S. military carries out drone strikes in Yemen from its base in Djibouti, while the CIA flies armed drones from a separate base in Saudi Arabia.

The CIA and the U.S. military have carried out 16 drone strikes in Yemen this year, according to the New America Foundation, which monitors the drone campaign. Last year, a record 54 strikes occurred.

The Pentagon said it will keep an undisclosed number of military personnel in Yemen to support the U.S. Embassy “and monitor the security situation.” U.S. military officials did not specify how many Americans were flown out of Yemen or where they were taken.

Residents in the capital reported seeing and hearing a low-flying aircraft that many believed to be a U.S. drone or some form of surveillance plane.

Raghavan reported from Nairobi. Craig Whitlock at Fort Bragg, N.C., Julie Tate in Washington and Ali Almujahed in Sanaa, Yemen, contributed to this report.

FBI hacking squad used in domestic investigations, experts say

Suzanne Choney NBC News

The FBI is using its own hacking programs for installing malware and spyware on the computers of suspected terrorists or child pornographers, a tactic that is drawing attention in the wake of disclosures about the domestic online surveillance of Americans.

Among the programs is one known by various names, including the Remote Operations Unit and Remote Assistance Team, which uses private contractors to do the actual hacking of suspects. The contractors can send a virus, worm or other malware to a suspect's computer, giving law enforcement control of a wide range of activities, from turning a computer's webcam on and off to searching for documents on the machine, says Christopher Soghoian, principal technologist for the ACLU's Speech, Privacy and Technology Project.

"In the last few years the FBI has created a team that has solely focused on delivering what we call malware — viruses and worms — to people's computers to get control of them," he told NBC News.

The FBI was contacted Monday by NBC News for comment, but has not yet responded. If we hear back, we will update this story. The agency, believed to be behind a recent large-scale malware attack, declined to comment to the Wall Street Journal about the hacking issue. Meanwhile, CNET reports that the FBI has reportedly developed software to help intercept "metadata" — information like the websites visited and email addressed used by an individual — and it wants Internet providers to allow the agency to install the software, but is meeting with resistance.

Mark Rasch, former head of the Department of Justice's Computer Crimes Unit who has worked with the FBI in the past, said the existence of the hacking team is well-known, and that there are other similar teams, coordinating with private contractors.

"There's a whole bunch of groups in the FBI that do this," Rasch, now an independent consultant, told NBC News. "There's one that interfaces with telephone companies, another with Internet providers. These guys make 'critters' — malware, a bug, virus, a worm — that can infect the computer, the cellphone ... any kind of communication device."

However, he said, the FBI is obtaining court-approved warrants or wiretap orders to do the surveillance.

"If I'm going to turn on your camera on your laptop, I'm going to need to go through the same legal process that I would need in order to install a camera in your house," he said. "There are exceptions to the warrant requirement, but I would be surprised if they were doing this without a warrant or some kind of legal process."

Soghoian said he is not so sure that is the case. "We don't know much about what legal standards they follow," he said.

Earlier this year, he said, "we learned that the FBI had gone to a federal magistrate in Texas to ask for a warrant authorizing the delivery of malware that would take over a target's webcam, and download files from their computer. That judge said no, because he believed that covert webcam use required a wiretap order not just a warrant. The judge was also concerned that the government hadn't identified how it would make sure that only the court-approved target of the surveillance would be spied on, and not anyone else."

Alan Butler, appellate advocacy counsel for the Electronic Privacy Information Center, told NBC News that while the "government's access to hacking tools has been known for some time," until recently it "was not clear that they were being used in domestic criminal investigations."

"I don't think it is clear that a warrant or judicial order is sufficient to support the use of intrusive hacking tools," he said in an email. "These tools can cause damage to hardware and software, and allow the monitoring of personal communications and even audio-visual surveillance surrounding electronic device."

Butler believes the FBI's "authority to use these hacking tools has not been clearly established, and there should be a public review of the legality of this program."

Soghoian agrees. "What I'm focused on is that we haven't had a proper debate on this. There was no law giving the FBI authority to do this."

Rasch says the "real problem isn't the FBI or the law; it's technology," and the nature of malware, or "critters" that are "hard to control."

Malware does not discern who is using a device and the innocent may wind up getting hurt, or having their privacy invaded as collateral damage in cyber-spying.

"It's hard for me to write a virus that will only capture your actions on a computer without also capturing your kids using it to do their homework or your daughter getting undressed in front of a Web camera," he said.

Check out Technology and TODAY Tech on Facebook, and on Twitter, follow Suzanne Choney.

For that reason I suspect they will use this as a lame excuse to

allow the cops to arrest people for drunk walking, not for the safety

of the drunks, but to raise revenue for the government.

Drunk walking leads to pedestrians fatalities

Associated Press Mon Aug 5, 2013 4:35 PM

WASHINGTON — Just as drinking and driving can be deadly, so can drinking and walking. Over a third of U.S. pedestrians killed in 2011 had blood alcohol levels above the legal limit for driving, according to government data released Monday.

Thirty-five percent of those killed, or 1,547 pedestrians, had blood alcohol content levels of .08 or higher, the legal limit for driving, according to data reported to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration by state highway departments.

Among the 625 pedestrians aged 25- to 34-years-old who were killed, half were alcohol impaired. Just under half the pedestrians killed who were in their early 20s and their mid-30s to mid-50s were also impaired. Only among pedestrians age 55 or older or younger than age 20 was the share of those killed a third or less.

By comparison, 13 percent of drivers involved in crashes in which pedestrians were killed were over the .08 limit.

Overall, about a third of traffic fatalities in 2011 — 31 percent, or 9,878 deaths — were attributable to crashes involving a driver with a BAC of .08 or higher.

Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx released the data as he kicked off a new effort to reduce pedestrian deaths. There were 4,432 pedestrian fatalities in 2011, the latest year for which data is available. That was up 3 percent from the previous year.

Jonathan Adkins, a spokesman for the Governors Highway Safety Association, which represents state highway safety offices, said anti-drunk driving campaigns may be encouraging more people to walk home after a night of drinking.

Alcohol can impair pedestrians’ judgment and lead them to make bad decisions, like crossing a road in the wrong place, crossing is against the light, or “trying to beat a bus that’s coming,” he said.

There is no data on an increase in alcohol-impaired bicycle fatalities, but there has been discussion at safety conferences around the country about what appears to be the beginning of a trend, Adkins said.

Safety advocates have been warning for several years that they’re also seeing more cases of distracted walking. Several studies show that people who are talking on their cellphones while walking make more mistakes.

Licensed criminals: FBI informants authorized to break the law 5,600 times in one year

Published time: August 05, 2013 00:55

Edited time: August 06, 2013 09:30

In at least 5,658 cases in a single year alone, the FBI authorized its informants to commit crimes varying from selling drugs to plotting robberies, according to a copy of an FBI report obtained by USA Today.

After much redacting by the authorities, the watered-down FBI's 2011 report obtained under the Freedom of Information Act has revealed that agents had been authorizing 15 crimes a day on average, in order to get the necessary information from their informants.

The document does not indicate the severity of the crimes authorized by the agency, nor does it include material about violations that were committed without the government's permission. It just sites a number of 5,658 Tier I and II infractions committed by criminals to help the bureau battle crime.

According to the Department of Justice Tier I is the most severe and includes “any activity that would constitute a misdemeanour or felony under federal, state, or local law if engaged in by a person acting without authorization and that involves the commission or the significant risk of the commission of certain offenses, including acts of violence; corrupt conduct by senior federal, state, or local public officials; or the manufacture, importing, exporting, possession, or trafficking in controlled substances of certain quantities.”

The Tier II includes the same range of crimes but committed by informants acting without authorization from a federal prosecutor but only from their senior field manager in FBI.

In the past, the newspaper revealed, the violations ranged from drug dealing to bribery.

As an example of severe crime committed by an authorized informant, the newspaper references the case of James Bulger, a mobster in Boston who was allowed by the Federal government to run a gang ring in exchange for insider information about the Mafia. Since then, the US Justice Department ordered the FBI to track and record the wrongdoings of the informants, results of which are due annually.

The FBI remains secretive about its informants. It is known that in 2007, the FBI estimated that around 15,000 confidential sources were employed by the bureau.

The Justice Department has requirements in place which spell out the rules of engagement with informants and “otherwise illegal activity.” Authorization of violent crimes are not allowed by field agents and serious offenses must first be approved by federal prosecutors. But as the publication notes, the FBI’s Inspector General concluded in 2005 that the agency routinely failed to abide by those rules.

The FBI’s scheme to gather information using such methods is believed to be only the tip of the iceberg as other local, state and federal agencies also reportedly engage in similar practices. The FBI’s share of criminal prosecutions in court only amount to 10 percent of all criminal cases.

Meanwhile, a spokeswoman for the FBI, Denise Ballew, declined to comment the report saying only that the circumstances in which the bureau allows its informants to break the law are "situational, tightly controlled.”

From what I have read marijuana was re-legalized during WWII, not to help the troops get high, but because the hemp plant was used to make rope and canvas needed for the war.

Groundwork Laid, Growers Turn to Hemp in Colorado

By JACK HEALY

Published: August 5, 2013

SPRINGFIELD, Colo. — Along the plains of eastern Colorado, on a patch of soil where his father once raised alfalfa, Ryan Loflin is growing a leafy green challenge to the nation’s drug laws.

As part of regulation, Colorado will be able to randomly test hemp crops to ensure that they have only trace amounts of THC, a chemical in marijuana.

His fields are sown with hemp, a tame cousin of marijuana that was once grown openly in the United States but is now outlawed as a controlled substance. Last year, as Colorado voters legalized marijuana for recreational use, they also approved a measure laying a path for farmers like Mr. Loflin, 40, to once again grow and harvest hemp, a potentially lucrative crop that can be processed into goods as diverse as cooking oil, clothing and building material. This spring, he became the first farmer in Colorado to publicly sow his fields with hemp seed.

“I’m not going to hide anymore,” he said one recent morning after striding through a sea of hip-high plants growing fast under the sun.

Mr. Loflin’s 60-acre experiment is one of an estimated two dozen small hemp plantings sprouting in Colorado. Hemp cultivation presents a vexing problem for the federal government, which draws no distinction between hemp and marijuana, as it decides how to respond to a new era of legalized marijuana in Colorado and Washington State.

State agencies have worked quickly to create new rules, licenses and taxes for hemp and recreational marijuana. Many towns have voted to ban the new retailers; others have decided to regulate them. Denver, for example, is proposing a 5 percent tax on recreational marijuana sales.

Colorado has set up an industrial hemp commission to write rules to register hemp farmers and charge them a fee to grow the crop commercially.

“It’s something that can be copied and used nationally,” said Michael Bowman, a farmer in northeastern Colorado who sits on the state hemp commission. “We’re trying to build a legitimate industry.”

The state will also be able to randomly test crops to ensure that they contain no more than 0.3 percent THC, the psychoactive chemical in marijuana, far below the level found in marijuana.

Opponents say that hemp and marijuana are essentially the same plant and that both contain the same psychoactive substance. But supporters say that comparing hemp with potent strains of marijuana is like comparing a nonalcoholic beer with a bottle of vodka.

Still, farmers and marijuana advocates worry: will drug agents stand on the sidelines and allow Colorado and Washington to pursue their own experiments with legalization? Or will the federal government crack down to assert its authority over drug policies?

A spokesman for the Drug Enforcement Agency in Denver said hemp farmers were “not on our radar,” but R. Gil Kerlikowske, director of the Obama administration’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, has offered stern words against both marijuana and hemp, saying that no matter what states did, the plants were still illegal in the federal government’s view.

“Hemp and marijuana are part of the same species of cannabis plant,” Mr. Kerlikowske wrote in response to a 2011 petition that sought to legalize hemp cultivation. “While most of the THC in cannabis plants is concentrated in the marijuana, all parts of the plant, including hemp, can contain THC, a Schedule I controlled substance.”

Lately, hemp has been tiptoeing toward the agricultural mainstream, gaining support from farmers’ trade groups and a wide array of politicians in statehouses and in Washington. In the Republican-controlled House, a provision tucked into the farm bill would let universities in hemp-friendly states grow small plots for research.

A handful of states, from liberal Vermont to conservative North Dakota and Kentucky, have voted to allow commercial hemp. In Vermont, any farmers who want to register as hemp growers under a new state program have to sign a form acknowledging that they risk losing their agricultural subsidies, farm equipment and livelihoods if federal agents decide to swoop in.

Every year, the federal authorities seize and destroy millions of marijuana plants — a crackdown that has rattled the medical marijuana industry in California — but the pace of seizures has dropped sharply in recent years. In 2012, federal officials reported that 3.9 million cannabis plants had been destroyed under D.E.A. eradication efforts. A year earlier, officials said they had eradicated 6.7 million plants.

Beyond the risk of federal raids and seizures, Kevin Sabet, a former drug policy adviser in the Obama administration, said the market for hemp goods is still vanishingly small and questioned whether it could really be a panacea for farmers.

[This sounds like a drug warrior slinging the BS and saying negative stuff about hemp for the sake of demonizing it. From what I have read hemp is a much better industrial crop then cotton]

Ryan Loflin and other hemp farmers walk a precarious line, as the state said it would not authorize planting until next year.

“Hemp is the redheaded stepchild of marijuana policy, and probably for good reason,” said Mr. Sabet, who is now the director of the Drug Policy Institute. “In a world with finite capacity to handle drug problems, my advice would be for people to think less about an insignificant issue like hemp and more about the very real issues of drug addiction, marijuana commercialization and glamorization, and how to make our policies work better.”

[So don't grow this hemp for industrial purposes because it has the ability to get people high, even if you have to smoke a suitcase full of the industrial quality hemp to get high. Sounds like advice from a cops who needs the "drug war" to keep his high paying job arresting pot smokers]

Even without the threat of federal raids, transforming hemp into a cash crop will be like asking a clear sky for rain. Viable seeds are illegal and scarce. Few working farmers or experts in the United States have any expertise in growing hemp. And there is basically no infrastructure to process the plants into legal components like oil, fibers and proteins. [Well before 1937, when it was made illegal, hemp was routinely grown as an industrial crop.]

In Colorado, Jason Lauve, the executive director of Hemp Cleans, an advocacy group, said he has spoken with about two dozen small farmers and landowners who are cautiously growing their first hemp crops.

“We’re really walking gently,” Mr. Lauve said. “We don’t want to put people at risk. We want to see how much states’ rights really protect us, versus the jurisdiction of the federal government.”

Even here, farmers like Mr. Loflin are walking a precarious line. Although Colorado voters opened the door to hemp farming last year, the state warned would-be hemp farmers in May that they would not be authorized to plant until early in 2014.

But this spring, Mr. Loflin decided it was time. For years, he had read about how hemp could replenish undernourished soil and be woven and squeezed into a wide array of products. He drinks a shot of hemp oil for his health every day — “It tastes kind of like grass” — and believes the plant could one day lift the fortunes of struggling small farmers.

He spent the winter assembling a seed collection from suppliers in Britain, Canada, China and Germany, where hemp is legal. They entered the country via U.P.S., labeled “bird seed” or “toasted hemp seed.” One bag was seized by customs officials, he said. Some 1,500 pounds of seeds were not.

At the end of June, with more than $15,000 invested in the venture, he planted his crop. He said he alerted his neighbors and has not gotten any complaints from people around Springfield, or from federal officials.

When Mr. Loflin visits the farm from his home in western Colorado, he half-expects to see D.E.A. cars racing down Highway 160 to burn down his crop before harvest. But he believes he can stake a living in hemp’s oily seeds and versatile fibers. He has gotten tired of his day job building ski homes in the mountains. To him, hemp’s outlaw status is just another hazard of starting a business.

“It’s well worth the risk,” he said. “It’s hemp. Come on, it just needs to be done.”

Phoenix Suns’ Michael Beasley arrested in Scottsdale in drug possession

By Erin O’Connor and Matthew Longdon The Arizona Republic-12 news Breaking News Team Tue Aug 6, 2013 7:15 PM

Phoenix Suns forward Michael Beasley, already under scrutiny over sexual-assault allegations, was arrested Tuesday on suspicion of drug possession, according to Scottsdale police.

Police contacted Beasley at 1:15 a.m. for an alleged traffic violation near Scottsdale and McCormick roads.

An officer detected the smell of marijuana coming from the vehicle, and an undisclosed amount of narcotics located in the driver area were seized during a search of the car, Scottsdale police said.

Bickley: Is Beasley most pathetic player in Suns history?

Police arrested Beasley, 24, on suspicion of marijuana possession and he was released from custody. Scottsdale police said the officer determined Beasley was not impaired, but no further details were released.

It’s the latest legal issue for the Suns forward, who has yet to be cleared in a sexual assault case investigated by Scottsdale police. In January, a woman accused the basketball player and another man of assaulting her in Beasley’s home. No one has been charged.

Nearly two weeks after the claim was made, police cited Beasley for several offenses including speeding, driving on a suspended Arizona license, and driving without a vehicle license plate or registration.

Beasley has a history of drug abuse but claimed to have learned his lesson when he signed a three year, $18-million contract with the Suns in 2012. He went to rehab in 2009 after run-ins with police for marijuana. He was arrested again in 2011.

"I realized 10 minutes of feeling good is not really worth putting my life and my career and my legacy in jeopardy,” Beasley said at introductory press conference in 2012 after signing with the Suns. “I'm confident to say that that part of my career, that part of my life is over and won't be coming back."

Suns management did not respond to a request for comment.

A Kansas State University graduate, Beasley was a second-round pick for the Miama Heat in 2008, but spent more time off the court than on due to injuries. He was with the team for two seasons before being traded to the Minnesota Timberwolves in 2010.

Reporters Laurie Merrill and Paul Coro contributed to this article.

Arizona's medical marijuana law says people with medical marijuana prescriptions or recommendations are they are called can't be arrested for DUI simply because they have marijuana metabolites in their body, but the cops have decided to ignore

Prop 203

and arrest medical marijuana patients for DUI solely because they have microscopic traces of marijuana in their body.

I believe Arizona's DUI/DWI laws are among the strictest in the nation and if even a microscopic trace of marijuana is detected in your body you are consider guilty of drunk driving according to

ARS

28-1381

and

ARS 13-3401

3. While there is any drug defined

in section

13-3401

or its metabolite

in the person's body.

13-3401. Definitions

4. "Cannabis" ...

Legal fight brews on impairment in medical-marijuana DUIs

By JJ Hensley The Republic | azcentral.com Wed Aug 7, 2013 10:54 PM

Medical-marijuana cardholders in Arizona who drive after using the drug may face a difficult legal choice: their driver’s license or their marijuana card. If they use both, they could be charged with DUI.

Valley prosecutors say that any trace of marijuana in a driver’s blood is enough to charge a motorist with driving under the influence of drugs

[per ARS

28-1381.A

and

ARS 13-3401]

and that a card authorizing use of medical pot is no defense.

[per ARS

36-2802.D

- "a registered qualifying patient shall not be considered to be under the influence of marijuana solely because of the presence of metabolites or components of marijuana that appear in insufficient concentration to cause impairment"]

But advocates of medical marijuana, which voters approved in November 2010, argue that the presence of marijuana in a person’s bloodstream is not grounds for charging drivers who are allowed to use the drug.

[again per ARS

36-2802.D]

The legal battle over the rights of medical-marijuana cardholders to drive while medicating is being fought in the state’s court system. Motorists convicted in municipal courts, which typically rule it unlawful for a driver to have any trace of marijuana in his or her blood, are appealing cases to Superior Court, where judges’ decisions could set precedents for how the medical-marijuana law applies to Arizona drivers.

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia authorize the use of marijuana for medical purposes, making marijuana-related DUIs an issue for police, prosecutors and politicians nationwide.

The biggest issue is deciding what blood level of marijuana makes a driver impaired, similar to the way blood-alcohol levels determine when a person is legally drunk.

[Arizona's DUI laws say any microscopic trace of an illegal drug is an automatic conviction for DUI, but Arizona's medical marijuana law says this does not apply to people with medical marijuana prescriptions or recommendations]

In Arizona, the confusion over interpretation of the Medical Marijuana Act stems from its inception because prosecutors and police didn’t have the chance to weigh in before it went to voters in 2010.

[it's not confusion, police and prosecutors have decided to ignore

Prop 203

which says - "a registered qualifying patient shall not be considered to be under the influence of marijuana solely because of the presence of metabolites or components of marijuana that appear in insufficient concentration to cause impairment"]

Prosecutors say Arizona law allows motorists who are not impaired to drive with prescription drugs in their system if they are using them under doctors’ orders.

The problem for marijuana cardholders is that pot can’t be prescribed, only recommended, offering no legal grounds for a motorist to drive with even trace amounts of the drug in their system, according to prosecutors.

[wrong

Prop 203

very specifically excludes people with medical marijuana prescriptions - "a registered qualifying patient shall not be considered to be under the influence of marijuana solely because of the presence of metabolites or components of marijuana that appear in insufficient concentration to cause impairment"]

For most driving-under-the-influence-of-marijuana cases, the drug charge is secondary to the charge of driving while impaired. Arizona’s DUI laws have three aspects: driving while impaired to the slightest degree, driving under the influence of alcohol and driving under the influence of drugs.

The handful of cases making their way through the courts grew out of traffic stops, where drivers are typically cited for both driving while impaired to the slightest degree and driving under the influence of drugs.

Attorneys for the accused say they are willing to argue about impairment, which would allow a drug expert hired by the defense to counter testimony from a police drug-recognition expert, but that a suspect’s legal participation in the state’s medical-marijuana program should provide a defense to the DUI-drug charge if there is no evidence of impairment.

Prosecutors in Mesa and other jurisdictions have successfully argued to keep juries from hearing information about a suspect’s medical-marijuana card, which could be appealed.

“They can make that argument (about impairment) and I think it’s a fair one to make. What they can’t do is preclude a jury from hearing that he has a medical-marijuana card,” said Craig Rosenstein, an attorney representing a DUI-drug suspect in Mesa. “The idea that he would be able to beat the (DUI-drug) charge is impossible unless the jury can hear that they have a medical-marijuana card. Otherwise, he’s just a kid smoking weed and he got caught.”

Morgan Jackson Doyle, 24, was coming back from the Salt River on Memorial Day 2012 when he was stopped at a sobriety checkpoint by Mesa police near Power Road and the Red Mountain Freeway.

An officer said Doyle had reddened eyes and a raspy voice, which prompted him to ask whether Doyle had recently smoked marijuana, according to police.

Rosenstein, Doyle’s lawyer, said Doyle gave the officer his medical-marijuana card with his driver’s license, “out of an abundance of truth.”

Doyle was put through a series of field-sobriety tests, some of which indicated impairment while others did not, before a trained drug-recognition officer was called to put Doyle through more thorough tests that look for clues of drug use.

The drug-recognition expert determined it was not safe for Doyle to drive, police said. He was cited for driving while impaired to the slightest degree and driving under the influence of drugs.

Blood tests later showed Doyle had the psychoactive component of marijuana in his blood, but in an amount that falls below levels some scientists consider the threshold for impairment.

A judge in Mesa refused to allow Doyle to introduce the card at his trial, prompting his lawyer to seek a ruling in Superior Court, which sent the case back to Mesa. If the court rules as expected, attorneys said the case will be appealed.

“I think it’s ridiculous. Voters in Arizona adopted the Medical Marijuana Act, whether politicians agree, or not,” Rosenstein said. “My concern was, if this isn’t isolated to Mesa, in theory that could make bad law for the entire state.”

Phoenix prosecutors have taken the same stance on drug DUIs for marijuana cardholders, in part, because the drug does not come with any of the same controls as a standard prescription, said Beth Barnes, the city’s traffic-safety resource prosecutor.

The potency of marijuana can vary among dispensaries that sell to patients, and doctors’ recommendations do not have dosage limits and warning against operating heavy machinery that prescriptions usually carry, she said.

Those and other factors mean possession of a card is not relevant in DUI cases, Barnes said.

Aaron Carreón-Ainsa, Phoenix’s chief prosecutor, said he understands it is legal for authorized patients to use medical marijuana, but that right can infringe on other privileges they might enjoy.

“For those people who have medical-marijuana cards, OK, it’s legal. Fine,” Carreón-Ainsa said. “But don’t come to this building because you’ve been driving. Just take it and don’t drive.”

Blood concentration

Though some states have tried to attach a number to impairment, experts say the practice is complicated by a number of factors including the patient’s metabolism and smoking frequency.

A 10-year study of more than 8,700 DUI-drug cases in Sweden led researchers to conclude that zero-tolerance policies were probably most effective because they help identify suspects whose concentration-level might have fallen below an arbitrarily set limit while waiting to give a blood sample.

“Scientists have found it virtually impossible to agree upon the concentration of a psychoactive substance in blood that leads to impairment in the vast majority of people,” the researchers wrote.

Colorado legislators consistently rejected proposals to link impairment with a particular amount of marijuana in a driver’s blood, but this year passed a law allowing prosecutors to presume impairment if that level is above 5 nanograms per milliliter. Defense attorneys argue that 5 nanograms is an arbitrary amount that has no bearing on impairment.

“We need to stop looking at a meaningless number, and in the case of Arizona, not only a meaningless number but a cruel and unusual application of it: you punish somebody on a Monday morning for them killing their pain on a Friday night,” said Lenny Frieling, a Colorado attorney and medical-marijuana advocate.

“I don’t want impaired drivers on the road. The key in my mind is looking at whether somebody really is or is not impaired. If they’re impaired, I don’t care which drug impaired them.”

[but Arizona's DUI laws in ARS

28-1381

say that anybody with a detectable amount of an illegal drug is considered guilty of DUI even if they ARE NOT impaired - and a person can have marijuana metabolites in their body weeks after using marijuana]

Frieling is developing a mobile test that gauges factors, including memory and balance, that could help determine impairment, but without years of clinical trials and research about marijuana concentrations that equate to impairment, the issue often relies on police drug-recognition experts and interpretation of state laws.

Courts within the same states have been inconsistent in applying the law.

A Michigan man was charged with driving a car with a prohibited substance in his system after he told an officer during a traffic stop that he was an authorized medical-marijuana cardholder and had smoked five hours earlier.

A judge concluded that the state’s medical-marijuana law protected him from prosecution unless police could prove he was impaired. Another court agreed before the Michigan Court of Appeals reversed the judge’s order and determined that legislators deemed it unsafe for a motorist to drive with any amount of marijuana in their system.

The Michigan Supreme Court reversed that Appeals Court decision earlier this year and found that the state’s medical-marijuana law authorized participants to have traces of marijuana in their bloodstream so long as they were not impaired while driving.

The Michigan driver’s blood contained 10 ng/ml of the active marijuana metabolite — twice the limit adopted in Colorado — but the justices said the amount was not enough to constitute driving under the influence without evidence of impairment.

“The MMMA (Michigan Medical Marihuana Act) shields registered patients from the internal possession of marijuana,” the court ruled. “The MMMA does not define what it means to be ‘under the influence’ but the phrase clearly contemplates something more than having any amount of marijuana in one’s system and requires some effect on the person.”

Arizona’s medical-marijuana users should be afforded similar protections when they are not impaired, say the law’s supporters.

Andrew Myers, campaign manager for the organization that got the Arizona Medical Marijuana Act on the 2010 ballot, said law enforcement should not base an arrest solely on the presence of marijuana in a cardholder’s system.

“The presence of metabolites alone shall not constitute impairment under the law — period,” he said. He said the program’s language was “very mindfully” written to avoid cases such as the Mesa case.

“There’s absolutely no way that, if challenged in court, that a conviction would stand — the law is absolutely clear on this point,” Myers said. “You could medicate on a Friday and get pulled over on a Monday two weeks later. It’s that ridiculous — it would absolutely preclude any medical-marijuana cardholder from operating a motor vehicle at any time if they were an active patient. And that’s ridiculously onerous and it’s not reflective of reality for a person who medicates.”

Myers said law enforcement should propose legislation to establish a legal standard of impairment: “Until that point, I think the law needs to favor the citizenry,” he said.

[Arizona's medical marijuana law clearly says it is illegal to drive when stoned on marijuana, but it also says that you are not considered guilty of DUI simply because you have marijuana metabolites in your body.]

Kenya airport fire thefts: 7 police investigated

By TOM ODULA

Associated Press

NAIROBI, Kenya -- A government official in Kenya says seven police are under investigation for theft in the wake of a major fire at Nairobi's main airport.

Four officials told The Associated Press on Thursday that first responders to the fire stole electronics and money. Nairobi's arrival hall — which contains foreign exchange shops and banks — was destroyed by in Wednesday's blaze.

A government official Friday said an investigation was targeting seven police officers for theft. The official insisted on anonymity because he wasn't authorized to share the information.

Public servants in Kenya, including police, firefighters and soldiers, are poorly paid and frequently accused of corruption. Police officers who guard the entrance to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport are well known for demanding bribes from taxi drivers and private vehicles.

For years Sheriff Joe Arpaio's goons in the Maricopa Sheriff's Offices have done there best to terrorize Latinos in the Phoenix metro area and it looks lie that racism in government pays rather well.

Pay hike to $182,145 for Arpaio’s chief deputy approved

By Michelle Ye Hee Lee The Republic | azcentral.com Wed Aug 7, 2013 10:06 PM

The Maricopa County Board of Supervisors on Wednesday approved a raise for sheriff’s Chief Deputy Jerry Sheridan, increasing his annual salary to $182,145.

Sheriff Joe Arpaio requested the board to bump Sheridan’s salary an extra 4 percent after Sheridan received the average salary increase of 5 percent last month during countywide merit raises.

The board unanimously agreed.

The supervisors are supporters of Sheridan and the role he has played in recent years to mend relationships among the board, the Sheriff’s Office and the County Attorney’s Office.

Just over two years ago, Arpaio named Sheridan as No. 2 after the embattled former chief deputy was fired.

“It’s very appropriate, what we’re proposing to pay Chief Sheridan,” board Chairman Andy Kunasek said.

Florida teen dies after being shocked by police

Associated Press Thu Aug 8, 2013 7:52 AM

MIAMI BEACH, Fla. — Miami Beach police say an 18-year-old died after being shocked with a stun gun as he resisted arrest for spraying graffiti.

Chief Ray Martinez told the Miami Herald (http://hrld.us/19bL8Wz ) that officers spotted Israel Hernandez-Llach painting graffiti on an abandoned fast-food restaurant early Tuesday. Martinez said the teen ran, but was eventually cornered. He said Hernandez-Llach then ran at the officers and one shot him with a Taser in the chest. The teen went into medical duress and died at a hospital.

The teen’s friends told the Herald that Hernandez-Llach was originally from Colombia. His teachers at Miami Beach High School said he was a talented artist and photographer.

Teen graffiti artist dies after Tasering by Miami Beach cops

BY JULIE K. BROWN

jbrown@MiamiHerald.com

At just 17, Israel Hernandez-Llach was already an award-winning artist, on the threshold of acclaim in Miami Beach art circles. He was a sculptor, painter, writer and photographer whose craft was inspired by his home country of Colombia and his adopted city, Miami.

He was also a graffiti artist, known as “Reefa,” who sprayed colorful splashes of paint on the city’s abandoned buildings while playing cat-and-mouse with cops, who, like many, consider graffiti taggers to be vandals, not artists.

It was while spray-painting a shuttered McDonald’s early Tuesday morning that Hernandez-Llach was chased down by Miami Beach police and shot in the chest with a Taser. He later died.

Miami Beach Police Chief Ray Martinez said Hernandez-Llach was confronted by officers about 5 a.m. as he was vandalizing private property, and he fled, leading officers on a foot chase. It ended at 71st and Harding when he was cornered by police and ran toward the officers, ignoring commands to stop, Martinez said.

“The officers were forced to use the Taser to avoid a physical incident,’’ the chief said.

He was hit once in the chest and collapsed, Martinez said, at which point officers noticed he was showing signs of distress. He was transported by fire-rescue to Mount Sinai Hospital, where he was later pronounced dead.

“The city of Miami Beach would like to extend their condolences to the family of Israel Hernandez,’’ Martinez said. The death remains under investigation by the city and the state attorney’s office.

Tasers are considered a nonlethal weapon, and police say their use has greatly reduced the number of fatalities in confrontations between police and violent subjects. Deaths after a Tasering are uncommon — but they do happen. Often an autopsy will discover that the Tasered individual had either a pre-existing medical condition or drugs in their system.

The medical examiner did not rule on a cause of death following an autopsy Wednesday. Further tests are pending, but Martinez said Hernandez-Llach did not suffer any other injuries. Martinez said Hernandez-Llach’s only previous arrest was for shoplifting, and that there was no indication he was involved in gang activity.

At the family’s apartment in Bay Harbor Islands Wednesday evening, a group of family and friends were tearfully coming to grips with their loss. Arranged carefully on a table in the apartment: an array of the young man’s drawings, sculptures and awards.

“He wanted to change the world somehow through art,” said the teenager’s 21-year-old sister, Offir Hernandez. “We want answers. We only want to know what happened.”

The family’s lawyer, Todd McPharlin, said his clients would like an independent investigation of the incident.

The police report goes into great detail about the wild pursuit to catch Hernandez-Llach, who led officers into alleyways, past apartment buildings, into doorways and down hallways. He jumped a fence, landed on the hood of a parked car, then, the police report said, lost his footing and fell on his chest — before taking off yet again.

“Two seconds after losing sight of the subject I heard an unknown unit on the radio advise that the subject was in custody,’’ officer Thomas Lincoln wrote in his report. “I began walking north on Harding Avenue to 71st Street where I observed the subject sitting on the ground and against a wall.’’

Lincoln said paramedics were being called, but the officer did not say why in the report.

Tracy West, a parent who knew Hernandez-Llach well, said he was a “fantastic person and artist.” He was very thin, almost fragile, she said, hardly capable of posing a threat to police.

“He had been warned before by police that if they caught him again they would beat the s--- out of him,’’ West said. “He could not have done anything. All he thought about was art.’’

Herb Kelly, one of his art teachers at Miami Beach High, said “it was an honor to work with him.’’

He said a number of his pieces were exhibited at various galleries and museums in the area and he was very active at networking.

“He was cutting edge. He had such awesome potential. To lose his life the way he did is tragic.’’

Kelly said the teen was inspired by Miami Herald photographer Carl Juste, whom he met when he spoke to one of his classes.

“He was a photographer too, and was going to try to show Carl some of his work,’’ Kelly said.

His best friend, Tracy West’s daughter Eleanor, said he was born in Colombia and moved to this country when he was 13 or 14. He immediately fell in love with Miami, she said, and said he never planned to leave.

He had recently launched a line of skateboards that he designed and hoped to market under the name “Tropical,’’ and was completing an online course to earn his high school diploma.

“His art was everything to him,’’ she said.

Miami Herald writer Katia Savchuk contributed to this report.

I suspect it's also a government welfare program for the companies that tow cars, which you can become a part of by giving a bribe, oops, I mean a campaign contribution to your local politician.

Immigrants rights groups urge changes in car impound policies

By Kate Linthicum

August 7, 2013, 9:10 p.m.

Immigrant rights groups are calling on the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and other police agencies to stop impounding the cars of unlicensed drivers.

A 2011 state law requires police at drunk-driving checkpoints to give unlicensed drivers the chance to call someone with a license to take the car before it is towed.

But that law does not apply to routine traffic stops, and activists complain that unlicensed drivers across the county are losing their cars after being pulled over for minor infractions, such as making a wrong turn or driving without a seat belt. In many cases, the cars are impounded for 30 days at a fee of more than $1,000.

Activists say impound policies unfairly target immigrants here illegally, who cannot obtain licenses in California. At a news conference Wednesday held by a group called the Free Our Cars Coalition, Mexican immigrant Alma Castaneda said she and her husband have had their cars impounded five times for unlicensed driving. Three times they have not had the cash to pay the impound fee, she said, and have been forced to give up their cars to the lot.

Castaneda and other members of the coalition are asking immigrants to share their stories about impounds on a website in hopes of pressuring police departments around the county to make changes.

That is how immigrant rights groups persuaded the Los Angeles Police Department to make major changes to its impound policy, said Zach Hoover, a Baptist minister who leads an alliance of religious and community groups called LA Voice.

The number of vehicles impounded by the LAPD fell 39% last year from the year before, after the department enacted rules prohibiting officers from seizing cars at routine traffic stops if a licensed driver was available to take the car, according to department officials. The rule that required cars to be kept in impound lots for 30 days was also changed; now drivers can retrieve their vehicles as soon as they pay the impound fee.

The new rules drew lawsuits from the Los Angeles Police Protective League, which represents rank-and-file officers, and from a national group called Judicial Watch that said the policy is unfair to taxpayers. California State Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris issued an opinion that the LAPD's impound policies were legal.

But impounding after routine traffic stops remains common in other parts of L.A. County, the coalition said. Gerardo Leon, a Mexican immigrant in the country without legal permission who lives in Canoga Park, said he was stopped by a sheriff's deputy Tuesday on his way home from work. The deputy told him he had been driving too close to another vehicle.

Leon produced evidence of insurance but did not have a license. He was issued a ticket, and his car was towed to an impound lot, where it must remain for 30 days. He said he was not given the opportunity to call a licensed friend to take the car. He doesn't know how he'll get to his job at a construction company, which is 25 miles away from his home.

L.A. County Sheriff's Department spokesman Steve Whitmore said Sheriff Lee Baca issued a directive several years ago "that made it clear his priority isn't to impound vehicles." But Whitmore said he didn't know if the directive applies only to unlicensed drivers stopped at sobriety checkpoints, or whether it pertains to all traffic stops.

He said he thought a new review of the policy was likely and urged anybody who felt they had been treated inappropriately to file a complaint.

Whitmore suggested Baca is open to changing the policy. "It is not our intention to impound vehicles if we don't have to," he said.

kate.linthicum@latimes.com

Mothers to protest firearms on transit

By Alia Beard Rau The Republic | azcentral.com Thu Aug 8, 2013 11:09 PM

It’s against the rules to eat, drink from cups without lids and swear on public transportation in Arizona. But passengers can carry their guns on board a bus or light-rail train.

Arizona has some of the most gun-friendly laws in the nation, allowing owners to carry concealed weapons without a permit and limiting where and when local governments can ban firearms. With a few exceptions, such as on school grounds, the state and local governments can ban firearms in public buildings or vehicles only if they provide gun owners with secure temporary storage.

There are no gun lockers on Arizona buses or light-rail trains.

“Our policy is we prefer that no passengers carry weapons or firearms, and we have posted notices that I’ve seen on buses that do say, ‘No guns,’ ” said Susan Tierney, communications manager for Valley Metro. “But we really can’t enforce that.”

[Many years ago guns were banned from Valley Metro buses. But I suspect they were threatened with a lawsuit and the ban on guns was removed. I suspect the old policy was a violation of the 2nd Amendment, and the Arizona law which requires the government to let you store your gun if guns are banned in a public place.]

A group of moms hopes to change that.

Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America is hosting a “stroller jam” protest on the light rail in Tempe on Saturday to bring attention to state gun laws. At 11 a.m., the mothers will ride the train from the station at Apache Boulevard and Price Road to the stop at Mill Avenue and Third Street.

The protest is in response to a passenger who was recently seen riding a Tucson bus and carrying an AR-15 rifle. It will be a plea to the state Legislature to consider toughening the laws, said Kara Pelletier, leader of the national group’s Arizona chapter.

“We don’t believe a mom on the light rail should have to be deciding whether the guy boarding with an AR-15 is going murder her and her children or is just on his way to his friend’s house,” Pelletier said.

She said public transportation needs to be considered differently than any other location.

[Why should the Second Amendment be null and void on public transportation???]

“It’s one thing to say that private businesses can decide whether to allow people carrying guns into their place of business if they want to. Customers can vote with their feet,” Pelletier said. “But public transportation is taxpayer-funded. And, for some people, they have no alternative to that.”

[Sorry madam, the 2nd Amendment is intended to protect us from our government masters, like the bureaucrats that run public transportation]

She said the group is working with several Democratic state lawmakers on possible legislation for next session.

Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Phoenix, said he has spoken with the group generally about some options but had not discussed any legislation that would specifically ban guns on public transportation.

“We have to look at our gun laws in a comprehensive manner with public safety in mind while still preserving gun liberties,” Gallego said.

[Translation Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Phoenix wants to flush the Second Amendment down the toilet and ban guns]

Pelletier said her group is also pushing for more state oversight of who is carrying guns. Members favor expanding background checks or restricting the rights of domestic-violence offenders.

“We want to see laws passed that make it so if a guy does get on a bus with an AR-15, I can be assured he’s a good guy,” she said.

[Maybe we should ban cops from buses. They routinely murder innocent civilians with their guns]

Tierney said she could not recall any problems that have resulted from individuals carrying guns on Valley Metro buses or light rail.

Charles Heller, co-founder of the Arizona Citizens Defense League, called the concern over guns on public transportation ridiculous. His organization has crafted several of the state laws loosening gun restrictions over the years.

“Why would anybody be concerned about a holstered weapon?” he said. “All these people with an irrational fear of weapons should seek treatment.”

He said most transit riders would be amazed at the number of people who ride the bus armed without the people around them ever realizing it.

Usually the only time cops are charged with crimes is when they

p*ss off their bosses, and I suspect in this case Officer Richard Chrisman

did something to p*ss off his supervisor and that is why

Officer Sergio Virgillo changed his mind about covering up the crime.

Testimony of Phoenix police officer’s partner attacked in murder trial

By JJ Hensley The Republic | azcentral.com Thu Aug 8, 2013 11:01 PM

Phoenix police Officer Sergio Virgillo feared his partner, Richard Chrisman, from almost the moment they walked into a south Phoenix trailer for a domestic-violence call that ended with an unarmed man dead and Chrisman accused of murder.

As Chrisman’s second-degree murder trial continued Thursday, Virgillo told jurors he thought his partner had committed a felony aggravated assault when he answered Daniel Frank Rodriguez’s request to see a warrant by putting a gun to Rodriguez’s head as the two officers entered the trailer during a domestic-violence call in October 2010.

Virgillo also said that once Chrisman stuck his service weapon into Rodriguez’s temple, Virgillo wanted to detain Rodriguez as a victim of aggravated assault instead of a suspect in domestic violence.

[What rubbish. I doubt if in the history of Phoenix, Arizona a honest cop has ever arrested a crooked cop while they are both on duty and the crooked cop commits crimes. The usual is what happened here, the allegedly honest cop stands by and does NOTHING]

Virgillo said he watched as Chrisman shot Rodriguez with pepper spray, yelled at Chrisman to shock Rodriguez with his Taser and tried to shock Rodriguez himself when Chrisman’s Taser didn’t stick.

[Sounds like Virgillo was a partner in this crime. And if he had been a civilian he would almost certainly have been charged with murder too]

Virgillo was then prepared to let Rodriguez ride away on his bicycle before Chrisman intervened, shot Rodriguez’s dog and then turned the gun on Rodriguez, at which point Virgillo said he turned his head.

“I couldn’t bear to see an execution,” Virgillo said under questioning from prosecutor Juan Martinez. “That is not a situation to shoot anybody.”

Chrisman is charged with second-degree murder, animal cruelty and aggravated assault.

Virgillo never asked for backup, nor for assistance with Chrisman, who Virgillo said “went rogue.”

[It sounds like Virgillo also went rogue]

“After seeing Chrisman put the gun to Danny’s head, I don’t know what could happen, it could be me next,” Virgillo said.

It was a long day on the stand for Virgillo, the key prosecution witness in Chrisman’s murder trial, as his statements were taken apart by a defense attorney in 90 minutes of tense testimony that appeared to cast doubts on Virgillo’s account.

Defense attorney Craig Mehrens walked Virgillo through what he said on the witness stand Wednesday and used the police veteran’s past statements in interviews and depositions to highlight contradictions.

Chrisman’s attorney claims the officer properly escalated the use of force against Rodriguez, going from physical contact to using pepper spray and a Taser before firing his weapon.

Virgillo struck a markedly different pose on the stand Thursday than he took earlier in the trail.

The 17-year police veteran had little trouble recalling key facts and events on Wednesday. But under cross-examination Thursday, Virgillo repeatedly asked to have his statements from one day earlier read back to him so he could be sure of what he said.

[Sounds like he doesn't remember what he said in the previous testilying session!]

“You honestly don’t remember what you told us yesterday about something?” Mehrens asked Virgillo after the court reporter read the transcript.

As the trial continued, Mehrens presented some of the contradictions he believes exist.

Virgillo told jurors he was standing inside the trailer when the shooting took place, but Mehrens played a clip of an interview Virgillo gave to a detective on the day of the shooting in which he said he was standing outside the trailer on the porch.

[This isn't the first time a cop has several different sets of facts depending on who he is talking to. I suspect at this point in time Virgillo was helping cover up Chrisman's crime]

Virgillo told Mehrens on Thursday that he never knew that Rodriguez’s mother, Elvira Fernandez, called 911 to report that her son had thrown something against a wall, causing her to fear for her life.

Chrisman’s attorney then pointed out that a Phoenix police detective told Virgillo that he had responded to a 911 call on the day of the shooting.

And when Virgillo said on Thursday that he “could definitely see” if Rodriguez had reached for Chrisman’s gun, as the accused former officer claims, Mehrens brought out another clip of an audio interview with Virgillo that directly contradicted that statement.

“From my angle, I could not see that,” Virgillo could be heard saying on the tape.

[I suspect that at this point in time Virgillo was trying to cover up Chrisman's crime]

Martinez came back in the afternoon and peppered Virgillo with questions that allowed him to explain some of the apparent contradictions Mehrens pointed out. Virgillo was not in a position to see Chrisman’s gun, he said, but he saw Rodriguez’s hands the whole time and he never reached for the officer’s weapon.

And Martinez present Virgillo with another chance to make a point on which he has not wavered or contradicted himself: When Rodriguez was shot, he was backing way from Chrisman with his hands up repeating “hey.”

“(Rodriguez) was compliant (right before he was shot),” Virgillo said.

But of course as usual our government masters think they are above the laws they expect us to obey. Several candidates — including David Lujan, Sal DiCiccio, Laura Pastor and Justin Johnson have broken the law.

Ballot photos are illegal, but don’t expect arrests in Phoenix

By Eugene Scott PHX Beat Fri Aug 9, 2013 11:14 AM

To show their support for candidates, some Phoenix voters have photographed their filled ballots for the City Council elections and shared them on Facebook.

According to an Arizona law, photographing your ballot is against the law.

State statute says it is a misdemeanor for someone to “show the voter’s ballot or the machine on which the voter has voted to any person after it is prepared for voting in such a manner as to reveal the contents, except to an authorized person lawfully assisting the voter.”

“We would ask people not to do that because that is sharing a secret ballot so to speak,” said Matt Roberts, spokesman for the Arizona Secretary of State, which oversees elections.

Officials at the Secretary of State Office’s want voters to honor the law, but they likely won’t pursue violators.

“It’s certainly not something that our office is going to be policing, but we do not recommend it,” Roberts said. “Going after people who are taking pictures of their ballot would certainly be burdensome.”

Elections officials fear that enforcing the statute could discourage people from participating in the political process, Roberts said.

“We certainly recognize the fact that people are excited about voting and sharing with their friends their political view in whatever race they’re casting their ballot in,” he said.

Several candidates — including David Lujan, Sal DiCiccio, Laura Pastor and Justin Johnson — have been tagged by supporters sharing their ballots. The filled out ballots show up on the candidates' Facebook timelines and are visible to their followers. Roberts discourages candidates from sharing the photos of other people's ballots with their followers.

“My official response is that certainly the Secretary of State’s office is recommending people not to do that,” he said.

Roberts said he was uncertain of the consequences for posting a photo of someone else’s ballot.

Follow us on @PHXBeat.

Seeking Answers After Youth’s Death in Police Stop

By NICK MADIGAN and LIZETTE ALVAREZ

Published: August 8, 2013

BAY HARBOR ISLANDS, Fla. — Israel Hernandez-Llach, a skateboarder and 18-year-old artist, was typically adept at dodging police officers while he tagged Miami Beach walls with his signature, “Reefa.”

But early Tuesday morning, after he rolled up to a shuttered McDonalds, his lookout with him, the police caught up with the teenager. Mr. Hernandez-Llach bolted, running through the streets and a building and over an iron fence, according to a report by the Miami Beach police. The officers ultimately stopped him, after firing a Taser to immobilize him, said Raymond A. Martinez, the Miami Beach police chief.

At 6:15 a.m., an hour after the police first spotted him, Mr. Hernandez-Llach, a former Miami Beach High School student and a Colombian immigrant, was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital. The teenager was in medical distress after being shocked by the Taser, Chief Martinez said, and paramedics were called.

Chief Martinez said that the cause of death had not yet been determined and that the department was waiting for autopsy and toxicology reports. Mr. Hernandez-Llach had no other injuries, the police said. The department is investigating.

On Thursday, Mr. Hernandez-Llach’s parents held a news conference and called for an independent investigation. The family’s lawyers pointed out that had Mr. Hernandez-Llach been arrested he most likely would have been charged with criminal mischief, a misdemeanor that seldom ends in jail time. The teenager’s only previous arrest had been for shoplifting, the police said.

“Those guilty of this must be brought to justice,” said his father, Israel Hernandez Bandera, who was a former Avianca pilot in Colombia, holding back tears as he spoke. “Not even animals deserve that kind of treatment.”

A friend of Mr. Hernandez-Llach’s, Thiago Souza, 19, who served as the lookout on Tuesday, said he saw the police officers giving each other high-fives after deploying the Taser.

Family and friends called for a vigil on Thursday night and for two more vigils on Saturday at the location where Mr. Hernandez-Llach was shocked with the Taser. They are also trying to raise money for his funeral, relatives said.

“Art is nothing to be killed for,” said Offir Hernandez, 21, the teenager’s sister.

The Miami Beach Police Department has faced scrutiny in recent years after a string of shootings and misconduct involving its officers. During Memorial Day weekend in 2011, eight Miami Beach police officers fired more than 100 bullets at an intoxicated motorist who was driving recklessly. Four Hialeah police officers also were involved.

The motorist was killed and four bystanders were wounded. More than two years later, the case is far from resolved. The Miami-Dade state attorney is weighing whether to bring charges against the officers.

Tasers are used by an estimated 17,000 law enforcement agencies around the world to subdue people who pose a threat, according to Steve Tuttle, a spokesman for Taser International.

A 2011 Department of Justice report found that the devices are considered safe for a vast majority of those who are subjected to them and can save lives by immobilizing suspects. Taser use results in few injuries, the study found. Although people have died, the risk is extremely low, the report stated. Often, deaths are associated with pre-existing medical conditions, drug use or a subsequent fall. Continuous or repeated shocks are also associated with deaths, the report stated.

An estimated 500 people have died after being shocked by Tasers since 2001, according to data compiled last year by Amnesty International.

Jacqueline Llach, Mr. Hernandez-Llach’s mother, described her son as frail; friends said he was skinny and about 5 feet 10 inches.

“The police could have done what they needed to do without killing him,” she said in her apartment, where friends had gathered to console the family.

Even in his native Barranquilla, Colombia, Mr. Hernandez-Llach had a knack for art, friends said. His talent flourished when he arrived in the United States. At Miami Beach High School, he won awards for his painting and recently had two sculptures accepted in a temporary exhibit at the Miami Art Museum, said Savannah Diaz, a friend and fellow student.

His artwork was on display at his parents’ apartment in Bay Harbor Islands, just off Bal Harbour.

The teenager, who enjoyed pushing the boundaries of self-expression, also gravitated to photography and graffiti, Ms. Diaz said. She said he and his helpers would look for wall space in different corners of Miami, including Wynwood, which is known for its graffiti art, and Broward County.

Ms. Diaz, who graduated this year, said that her friend was not aggressive. “Israel is the most creative person any of us had ever met,” she said. “His life revolved around art and skating.”

Recently, he had started designing specially shaped skateboards.

This May, when friends graduated from Miami Beach High, Mr. Hernandez-Llach was not one of them. He had failed physical education, a subject he disliked, friends and family said.

“That’s Israel,” Ms. Diaz said. “P.E. wasn’t a priority. It was about his art work.”

Nick Madigan reported from Bay Harbor Islands, and Lizette Alvarez from Jacksonville, Fla.

Sorry Mr. President, there already is an "outside task force" to balance civil liberties and security issues.

It's called the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Of course you probably flushed it down the toilet after you used the Bill of Rights to wipe your *ss!!!

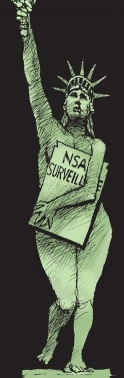

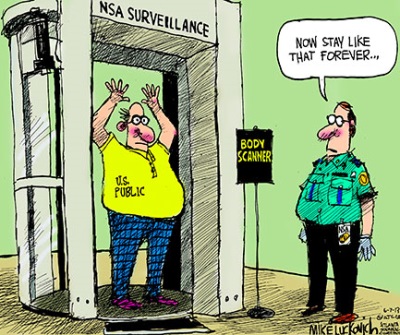

Obama unveils efforts to increase transparency on surveillance

By Holly Bailey, Yahoo! News | Yahoo! News

President Barack Obama unveiled new efforts to increase transparency and “build greater confidence” about the government’s controversial surveillance efforts, acknowledging that the public’s trust has been shaken after former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked operational details about the programs.

“It’s not enough for me as president to have confidence in these programs,” Obama declared at a White House news conference. “The American people have to have confidence as well.”

Among other things, Obama called for the creation of an outside task force to advise his administration on how to balance civil liberties and security issues. He also said he had directed the intelligence community to make as much information about the spying programs as possible and directed the NSA to create a website that would be a “hub” for that information.

“These steps are designed to make sure the American people can trust that our interests are aligned with our values,” Obama said.

Asked about his decision to cancel a September summit with Russian President Vladmir Putin, Obama admitted Moscow’s decision to grant Snowden asylum played a role in that decision, but insisted it wasn’t the only factor. He pointed to differences on Syria and human rights and said he believed it was more helpful to “take a pause, reassess where Russia’s going” and “calibrate the relationship” before meeting with the Russian leader.

“The latest episode is just one more in a number of emerging differences that we’ve seen over the last several months,” Obama said.

Obama announces NSA reforms, takes questions at news conference

By Steven R. Hurst Associated Press Fri Aug 9, 2013 1:09 PM

WASHINGTON — President Barack Obama announced a series of steps Friday meant to ease fears about the scope of secret domestic and foreign surveillance activities, saying he is confident the programs are “not being abused” but that they must be more transparent.

He gave no indication he was ready to end the massive collection of information about Americans’ telephone calls and email.

[This is typical of our lying double talking politicians. They have one press conference to say they are FOR something and then another press conference to say they are AGAINST the same thing. I suspect it works and people believe the version that they wish was true. As opposed to hearing both conflicting stories and realizing that one way or another the politicians are lying to us.]

In his first press conference since April, Obama also explained his decision to cancel a summit meeting next month with Russian leader Vladimir Putin and said he had only “mixed” success in moving forward in resetting the relationship between the two countries.